MIL-HDBK-61A: CM Life Cycle Management and Planning

< Previous | Contents | Next >

4.3 Government Management and Planning Activities

The Government's management and planning activities are common to all phases of the program life cycle, although the details upon which that management activity focuses varies from phase to phase. The global activities are illustrated in Figure 4-4 and described below. The details upon which they focus are described in the CM templates [See 4.4], and in referenced supporting paragraphs in this section, Sections 5-9, and appendices.

During each phase of the program life cycle, preparation for the following phase takes place. For concept exploration phases this work takes place prior to the initiation of the conception phase, when the requirements for funded study efforts are being formulated.

CM planning is a vital part of the preparation for each phase. CM Planning consists of determining what the CM concept of operation and acquisition strategy for the forthcoming phase will be and preparing or revising the Government's Configuration Management Plan [Details Appendix A] accordingly. Configuration Managers must envision future phases and determine what information in the current and immediately following phase must be captured to meet the needs of those future phases.

The CM concept of operation answers questions such as:

-

What are the CM objectives for the coming phase?

-

What is the rationale for these CM objectives?

-

How is each CM objective related to program objectives and risks?

-

What is the risk associated with not meeting the objectives?

-

How can achievement of the objectives be measured?

-

What information is required to support the Government CM goals for the next phase? Future phases?

-

How can that information best be obtained?

The CM acquisition strategy addresses the roles and responsibilities of the Government CM activities and the contractor CM activities by answering such questions as:

-

What are the deliverables from the next program phase?

-

Which deliverables are configuration items? Will contractors propose candidate CIs? How will the final listing of CIs be officially designated?

-

What is the end use of each CI?

-

How are they to be supported?

-

To what extent will the Government and the manufacturer support them?

-

To what level are performance specifications required? CIs? Repairable components? Replaceable components?

-

Will the Government prepare performance specifications, or will contractors?

-

Who in the contractor organization will be responsible for approving the performance specifications? In the Government organization?

-

What level of configuration documentation (e.g. performance specifications, detail specifications, complete technical data package) will the Government and the Contractor require by the end of the next phase?

-

What kinds of configuration identifiers (e.g., part numbers, serial numbers, nomenclature, National Stock Numbers) will the Government and the contractor require by the end of the next phase?

-

Which baselines (and documents) will already be subject to Government Configuration Control at the start of the next phase?

-

What baselines will be established by the contractor during the next phase?, Functional?, Allocated?, Product?

-

What documents need to be included in those baselines?

-

Will control of any of the baseline documents transfer from the contractor to the Government during the next phase? When is the transfer planned to occur?

-

What status accounting will be needed in the next phase?

-

Which specific information should the Government provide? Which specific information should the contractor provide?

-

Does the program have approval to obtain the information in other than digital format? Will the Government need to have on-line access?

Obviously these questions can not and should not be answered in isolation. They require close coordination, preferably in a teaming atmosphere involving Government Program, Engineering, and Logistic personnel. Where feasible it is desirable to work out planning for future phases within a teaming arrangement with the contractor or contractors participating in the current phase. This provides an opportunity to examine all perspectives on the critical issues and goals in an open atmosphere, and to arrive at an optimum approach.

In addition to enabling the Government CM manager to complete his CM plan, the answers to these questions also provide a rational basis for developing and coordinating configuration management and data management requirements to appear in requests for proposal, and in formulating the criteria to be used to evaluate proposals submitted by contractors. The RFP should be compatible with the Government's CM Plan, however the CM Plan should have sufficient flexibility to enable the CM strategic goals to be met with a variety of responses from contractors.

The RFP also must send the message to the contractor's that the Government is serious about configuration management. It is also one of the best opportunities for the Government CM manager to establish an environment in which contractor CM will have the support of its management. The proposal evaluation criteria (Section L of the RFP) should have Configuration Management as a key management and past performance discriminator. Its weighting should reflect the significance that an effective, documented contractor CM process can have in mitigating risk.

Preparation for the next phase is not complete until the Government CM Manager determines, and gains commitment for, the resources and facilities that will be needed to implement the Government's CM process. The infrastructure requirements must be adequate to support the program in accordance with the CM concept of operation, and acquisition strategy. The goal is to perform a credible risk analysis in developing the concept of operations which will provide convincing evidence to justify the investment in the CM process by showing that the investment will be returned many fold as a result of reduced costs for technical and logistic problems.

During each program life cycle phase, the Government CM Manager implements the planned CM Process. [Details 4.4] Preparing procedures and coordinating them with all participants in the process completes the process definition that was initiated in the CM planning activity preceding the phase. Neither Government, nor contractor Configuration Management can be accomplished effectively without the participation and cooperation of many different functional activities. There is no single CM function that does not involve at least two or more interfaces.

To accomplish the CM goals requires "team play". One of the best ways to achieve team play is to provide the vision, and solicit cooperative constructive input on the details of the implementing procedures. Each functional area must understand the particular roles and responsibilities that they have in the CM process. The tasks that they are to perform must be integrated into their work flow and given high priority. Coordinating the procedures is the initial step.

Any changes in the Government infrastructure necessary for the performance of CM during the phase are accomplished and tested, including the installation of appropriate automated tools and their integration with the data environment. Personnel from all disciplines and/or integrated product teams are then trained in the overall process and in the specific procedures and tools that they will use. Training pays dividends in a smooth seamless process in which personnel, who understand their roles and the roles of others with whom they interface, work cooperatively treating each interfacing player as a "customer".

Once all of these elements are in place, managing the CM process in the environment of performance based acquisition, IPTs and allocated configuration control authority, still remains a challenging enterprise. The individual IPTs, contractors and other Government activities who are the authority for configuration control of segments of the product design must apply consistent logic to their decision making, and must provide information that can be shared in the common data environment. Once a well thought out plan, and a documented and agreed- to process are in place, the Government CM Manager must employ modern management techniques to assess process effectiveness, assure anticipated results, and fine tune the process as necessary. It is also necessary to maintain the process documentation by updating plans, procedures and training, as required.

It all starts and ends with communication:

-

Articulating clear goals and objectives

-

Making sure that the various players understand and cooperate

-

Providing frequent feedback

-

Assuring that current status information, needed to complete process steps, is accessible, and

-

Paying attention to the inevitable minor problems which surface.

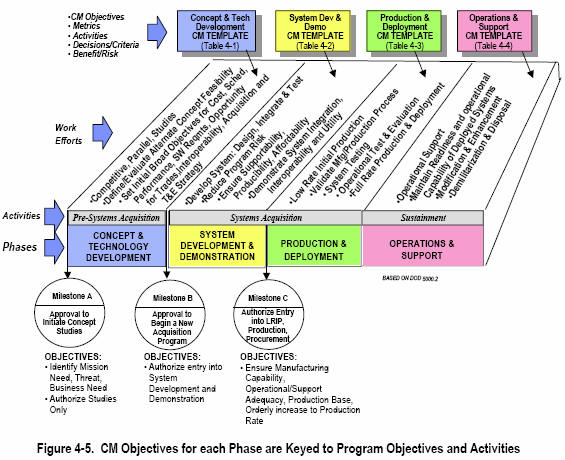

Both the Government and the contractor CM process are measured and evaluated using metrics, program reviews, and other means such as Contractor Performance Assessment Reviews (CPARS). Each template in Section 4.4 provides typical CM objectives for each phase, and typical metrics that may be selected to determine the degree to which those objectives (CM goals) are being met. The objectives help to focus the measurement on the most meaningful and important parameters; the metric presentation provides a level of confidence in the process being measured. Objective oriented metrics should be collected throughout the progress of the entire phase or at least until the stated objectives are realized. Figure 4-5 illustrates that CM objectives are related to the Program activity and Program objectives for each phase of the life cycle.

Since the CM Process is a shared enterprise, the Government CM objectives and the Contractor CM objectives should be congruent. The best way to do that is to communicate. During the CM planning for each phase, the Government must articulate the vision and the contractor must realize the seriousness of the intent. The Governments CM objectives should be made available to the contractor(s) for comment before being finalized. The Contractor's CM objectives should be provided to the Government for review as part of the contractor's proposal. The ensuing dialog can set the stage for effective CM implementation. Since the DCMC will be the agency to interface with the contractor most directly on metrics and performance measurement issues, they should be involved as a full team member. Ideally, all should agree upon a common set of objectives.

Metrics are key to continuous process improvement. Metrics constitute the data for improvement, i.e. the facts of the process. They enable problems that need attention to be quantified, stratified and prioritized and also provide a basis for assessing the improvements, and assessing trends. A properly constituted set of CM metrics supports both the CM goals and process improvement. Only a few critical items should be used at one time. They should be designed to positively motivate, rather than keep score, and should be forward focused (where are we going) not merely a compilation of past history.

CM by its very nature is cross functional. No important CM function is performed without interaction with other functional or team members. Therefore, CM objectives and measurements cannot and should not be divorced from the interacting systems engineering, design engineering, logistics, contracting and other program objectives and processes. Moreover, it is not the efficiency of CM activities, per se, that add value, but their result in contributing to overall program objectives.

Improving either the Government or industry CM process is a venture that typically requires interaction across a broad spectrum of program activities including technical, financial and contractual. The process must be documented to a level of detail that is:

-

Easily understood by all participants in the process

-

Focused on the key process interfaces

-

Less detailed than the procedures used to perform the process but sufficient to determine what must be measured to obtain factual information on the process.

A metric involves more than a measurement; it consists of:

-

An operational definition of the metric which defines what is to be measured, why the metric is employed, when, where and how it is used. It can also help to determine when a metric has outlived its usefulness and should be discontinued.

-

The collection and recording of actual measurement data. In the case of the CM process, this step can often be accomplished by query to the status accounting data base, which normally can provide a great deal of process flow information

-

The reduction of the measurement data into a presentation format (e.g., run chart, control chart, cause and effect diagram, Pareto charts, histogram) to best illuminate problems or bottlenecks and lead to the determination of root cause or largest constraint.

An effective metric has the following attributes:

-

It is meaningful in terms of customer relationships (where the "customer" can be any user of information that is provided.)

-

It relates to an organization's goals and objective, and tells how well they are being met by the process, or part of the process, being measured

-

It is timely, simple, logical and repeatable, unambiguously defined, economical to collect.

-

It shows a trend over time which will drive the appropriate forward focused action which will benefit the entire organization.

We learn from effective measurements and metrics if the process is or is not meeting objectives. We also learn which part of the process is currently the biggest contributor to detected backlogs, bottlenecks, repeat effort, or failures/errors. By focusing on that weakest link, we can isolate the problem and trace it to its root cause. Often the cause can be corrected by streamlining the process (eliminating redundancy or non-value adding steps, modifying sequence, performing tasks in parallel rather than in series) or improving communications. Measurements should continue as is or be altered to fit the new solution for a period of time sufficient to assess if the revised process is resulting in improved performance. This measurement/improvement cycle is an iterative process. Once a weak link is improved, the process metrics are again reviewed to determine and improve other parts of the process that stand out as contributors to deficiencies or lengthy cycle time.

The key personnel involved in the process must be participants in defining the improvements. Their "buy in" is essential if the improvements are to be implemented effectively. Detailed procedures and effected automated systems must be modified and personnel must be re-trained, as required. These "total quality management aspects" of the job are best performed as an integral part of the process of managing, rather than as isolated exercises. It is also foolish to expend effort in improving processes without clearly documenting the lessons learned to leverage the efficiency of future applications. Changes made in the process, over time, should be recorded along with the reasons the changes were made and the measured results. A suggested place to record process changes is in the configuration management plan. Initially the CM plan was a projection of the expected implementation of configuration management over the program life cycle. As a minimum, it is updated during each phase for application during the next. Including process change and lessons learned information makes the plan a working document reflecting the transition from anticipated action (planning) to completed action (reality). It can then serve as a better reference to use in planning for the next program phase and in the initial planning for future programs.

For correct application of this information, see NOTE on Contents page